Arabian Nights (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1974)

Italian Title: Il fiore delle mille e una notte

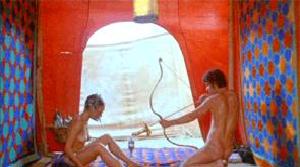

Arabian Nights is Pier Paolo Pasolini's final entry to his Trilogy of Life, consisting of filmed adaptations of classic literature, The Decameron (1971) and The Canterbury Tales (1972). The films in the trilogy are supposedly Pasolini's least political films, whose main intent is to straightforwardly tell the stories in the film medium without any social or political fuss. The trilogy also shows Pasolini in his most sensual, where his gift for poetry does not merely exist in the beauty of words but in lush colors, exotic locales, and sexual charge. It is said that Arabian Nights is the laurel in the trilogy, as it is the most beautiful and most lyrical of the films. I'd have to agree, Arabian Nights is a towering achievement in storytelling.

The film starts with a young boy purchasing a slave, but eventually falls in love with the slave he bought. The girl is kidnapped and finds herself in a kingdom where she is proclaimed king. The boy then travels all over looking for the girl, and on his way, meets different personalities with different tales. Arabian Nights does not use the literary source's means of telling the story, wherein a princess is tasked to tell stories for a number of nights. Instead, Pasolini celebrates the vibrancy of life by infusing the primary tale with the ability to give birth to different tales. The primary tale gives way to a tale, and a character from that tale, gives way to another tale, and so on, and in the end, everything wraps up beautifully and one gets a dreamy feeling of satisfaction one usually arrives at as a child.

However, Arabian Nights is nowhere near a children's story. It is in fact very graphic in its portrayals of the chosen entries of the literary source. Instead of repeating the stories of Aladdin or Ali Baba, Pasolini chooses the more sexually charged entries and depicts them with a candidness that makes the scenes both unusually magical despite the rawness of the topic. Yet again, Pasolini strays away from magic and religion. Although some of the tales do involve a certain element of mysticism (a demon flying and turning a curious human into a monkey, a metal-plated night being destroyed by a young man who follows a whispered prophecy), such is kept to a minimum and is balanced by a healthy dose of accurate anthropology and cultural diversity Pasolini mastered in the two films (Medea (1969) and Oedipus Rex (1967)) before the trilogy of life. Arabian Nights is delightfully accurate, with Pasolini not limiting his settings to Arabic palaces, deserts, but goes to far-off places like Nepal or Africa, where most of the original tales of the literary source were set.

Arabian Nights is truly a celebration of life for Pasolini. To a certain extent, I can probably declare this as Pasolini's accurate portrayal of his wet dream. The storytelling is vibrant and his visuals are full of bright colors. His characters are young and robust. The boys are laidback and inutile, lazy and oftentimes mainly instructed by hormones instead of intellect. The females are cunning and sly, some are virtuous and some are flirts. When the characters collide, one can easily predict that they will copulate, or at least engage in violent combat. Pasolini does not make room for his usual political discourse, but instead lets the images and the scenery depict his humanity. No wonder Pasolini decided to end his Trilogy of Life with this, a gorgeous and appetizing orgy of man's innate nature to tell stories.

0 comments:

Post a Comment